Ringstrasse

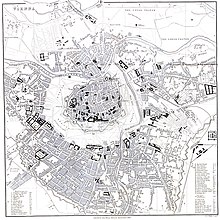

The Ringstrasse or Ringstraße (pronounced [ʁɪŋˌʃtʁaːsə] ⓘ, lit. ring road) is a 5.3 km (3.3 mi)[1] circular grand boulevard that serves as a ring road around the historic city centre, the Innere Stadt, of Vienna, Austria. The road is built where the city walls once stood. The Ring, as it is colloquially known, was built, along with grand buildings on either side of the road, in the second half of the 19th century. The road runs clockwise, from the Urania to the Schottenring, and is divided into nine parts.

Because of its architectural beauty and history, the Ringstrasse is designated by UNESCO as part of the Historic Centre of Vienna World Heritage Site.[2]

History

[edit]

The grand boulevard was constructed to replace the city walls, which had originally been erected during the 13th century. These walls were initially funded by the ransom payment obtained from the release of Richard the Lionheart, King of England, who had been captured near Vienna on his return from the Third Crusade. The fortifications were subsequently reinforced following the Ottoman Siege of Vienna in 1529 and the Thirty Years' War in 1618. The walls were surrounded by a glacis approximately 500 meters wide, where construction and vegetation were prohibited for military defensive purposes.[3][4]

By the late 18th century, these fortifications had become obsolete. Under the reign of Emperor Joseph II, streets and walkways were developed within the glacis, illuminated by lanterns and lined with trees. Craftsmen established open-air workshops, and market stalls were set up in the area. However, it was the Revolution of 1848 that brought more significant changes, leading to the eventual transformation of the space into the grand boulevard it is today.

In 1850, the suburbs, known as Vorstädte (now comprising Districts 2 to 9), were incorporated into the municipality. This expansion made the city walls an obstacle to traffic. Consequently, in 1857, Emperor Franz Joseph I issued the decree "Es ist Mein Wille", ordering the demolition of the city walls and moats. The decree not only ordered the removal of these fortifications but also detailed the dimensions of the new boulevard and specified the locations and functions of the planned buildings.[5]

Aristocrats and other wealthy private individuals rushed to have prestigious Ringstraßenpalais (Ring Road palaces) built in the historicist style, known as Ringstraßenstil (Ring Road style). One of the first buildings was the Heinrichhof, designed by Theophil von Hansen, which stood until 1954, having been damaged in the Second World War .

The construction work on the Ring was not finished until 1913 with the completion of the Minister of War, when the Ringstraßenstil had already become unfashionable, as shown by the Postal Savings Bank building opposite, built by Otto Wagner in Art Nouveau in 1906.[6]

The Ringstrasse and its accompanying structures were envisioned as a testament to the grandeur and glory of the Habsburg Empire. On a practical level, the construction of the Ringstrasse was influenced by Emperor Napoléon III's urban planning in Paris, where the widening of streets had proved effective in preventing the erection of revolutionary barricades, thus facilitating artillery control.

The greatest catastrophe on the Ringstrasse was the Ringtheater fire in 1881, which claimed several hundred lives. The Sühnhaus, a tenement, was built in place of the theatre, which in turn was destroyed in the Second World War and provided space for the new Vienna Police Headquarters to replace the previous police headquarters, which had also been destroyed.

Since the Ringstrasse was primarily designed for aesthetic purposes, a parallel thoroughfare known as the Lastenstraße (cargo road) was constructed on the outer edge of the former glacis. From 1907 onwards, tram lines with the number 2 ran along the street, which has been colloquially known as Zweierlinie (2-er Linie) since the 1960s.[7]

Use

[edit]

The Ringstrasse primarily serves as a major transportation route, playing a significant role in Vienna's road network. It is a three-lane, one-way road that operates in a clockwise direction. The road is serviced by public transportation, with the tram lines 1 and 2 running partly around the Ring. The two bike lanes on either side of the street are the two most-used bike lanes in Austria. However, these bike lanes have faced criticism from activists, as they are often interrupted by intersecting roads and are occasionally shared with pedestrians, leading to issues in tourist-heavy areas. [8]

As the Ring is home to many of Vienna's most famous sights, it attracts a large number tourists. Visitors often explore the Ringstrasse on foot, walking along footpaths on either side of the road, or undertake guided bus tours. The boulevard is also lined with numerous hotels and a variety of shops that cater to both local residents and international visitors.[9] Both the Kärntner Straße and the Mariahilfer Straße, two of Vienna's biggest shopping streets, lead into the Ring.[10]

The Ringstrasse frequently hosts political demonstrations and protests, including the annual Pride parade and International Workers’ Day demonstrations, as well as Fridays for Future and other climate-related protests. Demonstrations against the government are common, such as protests against the far-right led coalition talks in 2025, and anti-lockdown demonstrations during the COVID-19 pandemic. The road was the location of the July Revolt of 1927, when Austrian Social Democrats protested against the acquittal of three far-right nationalist paramilitary members for the killing of two Social Democrats.

Structures

[edit]The Ringstrasse runs clockwise, from the Urania to the Schottenring.

Buildings

[edit]

- Urania, an observatory

- Österreichische Postsparkasse (Postal Savings Bank), in Jugendstil by Otto Wagner

- University of Applied Arts

- Museum of Applied Arts

- Deutschmeister-Palais

- Gartenbauhochhaus with the Gartenbaukino (cinema)

- Café Schwarzenberg

- Grand Hotel Wien

- Opernpassage, a pedestrian underpass

- Hotel Imperial, a luxury hotel

- Vienna State Opera

- Hofburg, palace of the Habsburgs

- Kunsthistorisches Museum (Art History Museum)

- Naturhistorisches Museum (Natural History Museum)

- Palais Epstein

- Austrian Parliament Building

- Burgtheater (Court Theatre)

- Palais Lieben-Auspitz, with Café Landtmann

- Palais Ephrussi

- University of Vienna

- Votivkirche

- old Vienna Stock Exchange

- Ringturm

Parks

[edit]

- The Stadtpark, a 65,000m² park, cut in half by the Wien river, featuring statues of famous Viennese composers, including Johann Strauss II and Franz Schubert

- The Burggarten, behind the Hofburg, featuring a statue of Mozart and a greenhouse.

- The Volksgarten, part of the Hofburg palace

- The Rathauspark, infront of the town hall

- Sigmund-Freud-Park, infront of the Votivkirche

Monuments and Squares

[edit]

- Dr.-Karl-Lueger-Platz with Lueger memorial

- Radetzky monument

- Theodor-Herzl-Platz

- Schwarzenbergplatz with Schwarzenberg memorial

- Statues of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller facing eachover

- Maria-Theresien-Platz with a memorial of Maria Theresa

- Pallas-Athene-Brunnen, a fountain infront of the Parliament with a statue of Athena and Nike, as well as allegorical representations of the four most important rivers of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Danube, Inn, Elbe, and Vitava)

- The Republikdenkmal, a tribute to the founding of the Austrian Republic

- Liebenberg memorial, to mayor of Vienna Johann Andreas von Liebenberg

Sections

[edit]The Ring is split into 9 sections, most named after

- Stubenring (Stubenbastei fortification, part of the city walls from 1156)

- Parkring (Stadtpark)

- Schubertring (Franz Schubert, Viennese composer)

- Kärntner Ring (Kärntner Straße)

- Opernring (Vienna State Opera)

- Burgring (Hofburg)

- Dr.-Karl-Renner-Ring (Karl Renner, former chancellor and president), formerly Parlamentsring

- Universitätsring (University), formerly Dr.-Karl-Lueger-Ring (Karl Lueger, former mayor of Vienna)

- Schottenring (Schottenstift, a Benedictine monastery)

Franz-Josefs-Kai and Zweierlinie

[edit]

The Franz-Josefs-Kai, which runs along the Donaukanal, connecting either end of the Ring, is often included as part of the Ringstrasse. The road features two metro stations, Schwedenplatz in the square of the same name, as well as Schottenring. The Schwedenplatz is home to the popular Eissalon am Schwedenplatz, an ice cream shop, as well as being a part of Vienna's Bermudadreieck (Bermuda Triangle), a nightlife district in the inner city. The road offers multiple entrances to the city centre, including one path leading to St. Rupert's Church, the oldest church in Vienna.

The Ringstrasse is accompanied by a parallel street, the Zweierlinie, usually two to four blocks further out, which was largely built at the same time as the Ring. Buildings on the Zweierlinie include:

- Beethoven statue

- Akademisches Gymnasium, oldest secondary school in the city

- Konzerthaus, a concert hall

- Vienna Museum

- Musikverein, a concert hall

- Künstlerhaus Wien mit Albertina modern

- Secession, contemporary art exhibition hall

- Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

- MuseumsQuartier

- Volkstheater

- Palace of Justice, seat of the Supreme Court

- Rathaus, the town hall

- Rossauer Barracks, headquarters of the Defense Ministry

Gallery

[edit]-

Museum of Applied Arts

-

Hotel Imperial

-

Staatsoper

-

Museum of Art History

-

Parliament

-

Town hall

-

Burgtheater

-

University

-

Votivkirche

-

Old Stock Exchange

-

Ringtower

References

[edit]- ^ Vienna's Ringstrasse. Vienna: Sightseeing. Retrieved 2022-07-14.

- ^ "Historic Centre of Vienna". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2025-02-17.

- ^ Bousfield, Jonathan; Humphreys, Rob (2001). The Rough Guide to Austria. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-85828-709-6.

- ^ "From fortification to promenade". The World of the Habsburgs. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ "Die Entstehung der Ringstraße". wien.info (in German). Retrieved 2025-02-17.

- ^ "Austrian Postal Savings Bank building". www.visitingvienna.com. Retrieved 2025-02-17.

- ^ "Jahrhundertchance Zweierlinie". Die Grünen Wien (in German). Retrieved 2025-02-17.

- ^ "Die radfreundliche Ringstraße: So geht's!". Radlobby. 2024-05-27. Retrieved 2025-02-17.

- ^ "Vienna's Ringstrasse". vienna.info. Retrieved 2025-02-17.

- ^ georgscherer (2021-01-04). "Mariahilfer Straße: Die Wiederentdeckung der Füße". WienSchauen (in German). Retrieved 2025-02-17.

See also

[edit]- The Gürtel, a ring road around the inner-city districts.